One of the moments I was looking forward to most in my chronological playthrough of the Metal Gear franchise was the jump from The Phantom Pain to Metal Gear. This is a 28-year leap back in time from 2015 to 1987 that crosses an almost unbelievable technical gulf. I wanted to see what relation these two games had with one another and whether you can sense a continuity between them.

For those of you not steeped in Metal Gear knowledge, this is the first title in the series which launched on the MSX2 home computer in 1987. It’s known for pioneering the stealth genre, which came about by necessity rather than design due to hardware limitations on the number of bullets able to be displayed at once.

![]()

Working within these constraints (and drawing from a childhood love of hide and seek) a 24-year-old Hideo Kojima took over the project, knocked up a goofy little story about a soldier infiltrating Outer Heaven – a base where all is not as it seems – and the rest is history.

I played Metal Gear back in the run-up to the release of the fourth game in the late 2000s and was apprehensive about returning to it. I remembered a fiddly, unintuitive and ugly game that practically required a walkthrough to complete. I played it via MSX emulation, followed a guide to the letter, heavily relied on save states and was honestly glad to see the back of it.

![]()

This time I vowed to do better. I played the version included in the HD Collection port of Metal Gear Solid 3 and didn’t follow a walkthrough. I did reference maps of the levels, but that simply gave me clues on where to head next (and which keycards to use on which doors) rather than explicitly tell me what I need to do.

And wouldn’t you know it, focusing on the game and not flipping through a walkthrough made the whole experience much more fun. Even better, while it’s very dated you can absolutely detect the design ethos that’d be fully expressed in future games.

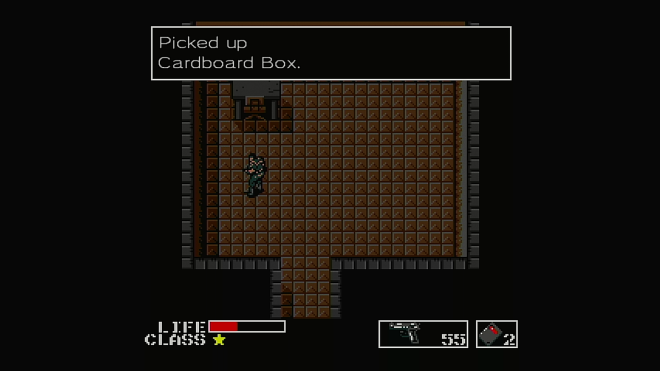

Most obvious is the cardboard box. This unassuming tool allows you to remain still and not alert guards and would go on to become an icon of the series. But here there’s also the remote-controlled missiles to disable electric floors, enemies being alerted through noise and the need to find a gas mask to get through noxious areas.

But the gameplay similarities go deeper than common tools. Despite Metal Gear‘s distance from The Phantom Pain you spend most of your time doing the same thing in both games: observing enemy movements, figuring out where their blind spots are and mentally plotting a route past them. This loop of observation, planning and execution (and rapid improvisation if it goes wrong) is at the heart of every Metal Gear game and is present and correct right from the first instalment.

![]()

Perhaps the only thing really lacking in Metal Gear is the series’ idiosyncratic personality. The bosses are pretty generic, announcing their names and attacking. Outer Heaven as a location is drab and dull-looking. Even Solid Snake and Big Boss (now retconned as The Phantom Pain‘s Venom Snake) are extremely two-dimensional characters (though they’re Mamet in comparison to the barely-there support team). But to be fair, it was made in 1987.

But you can see glimmers of what’s to come. Kojima’s predilection for breaking the fourth wall shines through in the late-game sequence when Big Boss orders you to turn off the game system. I particularly got a kick out of the HD Collection updating the dialogue for the PlayStation 3, meaning I had a character from a game released in 1987 and set in 1995 telling me to turn off a console from 2006.

![]()

And there are the touches that prefigure Kojima’s later obsession with details. For example, at the end of the game you must escape from the base before it self-destructs. You’re on a tight timer, but if you use the cigarettes in your inventory (which are useless up until now) you get extra time added on. I read this as being the more the player leans into the cool action hero stereotype, the less pressure you’ll be under.

It’s difficult to outright recommend Metal Gear to anyone other than a really dedicated fan. It hasn’t aged amazingly, offers no narrative insights you can’t get from reading a summary and isn’t a great looker. But this is the primordial ooze of Metal Gear and it’s fascinating to see the genesis of ideas that’d go so far.

Next up: Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake.

One thought on “Metal Gear (MSX2, 1987)”